Call for Papers: “Perfect Harmony“ and “melting strains“.

Music in Early Modern Culture between Sensibility and Abstraction

Music in Early Modern Culture between Sensibility and Abstractionat Humboldt-University Berlin, 1.-3. December 2011

In Early Modern culture, philosophers, musicians, theologians, and poets grappled with the ambivalent

nature of music. Music was perceived as a phenomenon occupying an ambiguous position between

mathematical abstraction and sensual experience. In the Pythagorean-Platonic tradition, music was

understood as euphonic mathematics replicating the perfection and beauty of a transcendent cosmic order.

At the same time, the emotive and physiological effects of actual musical experience proved it to be a

sensuous phenomenon of insistent immediacy and affective power.

The Classical concept of cosmic order and universal harmony based on the ratios and proportions of

musical intervals was still prominent in Early Modern thought. Mediated through Boethius, the idea

appeared in poetic texts as the trope of the music of the spheres; philosophical texts, such as the first edition

of Newton’s Principia mathematica (1687), often employed “musical” terminology.

The immediate physiological and psychological effects of music on the listener, meanwhile, were no

less important in the Early Modern discourse on music. Contemporaneous natural philosophical and literary

texts, as well as treatises on musical composition tried to come to terms with and gauge the affective power of

music. Texts concerned with the theory of composition – musica poetica – relied on classical rhetoric in their

endeavours to describe and prescribe the expressive and affective potential of musical figures.

The affective power of music, mediated through these figures, was important also in matters of

practical divinity, especially in the debate about church music and its liturgical function. St. Augustin, for

example, had already expressed his suspicions concerning the power of music over the body and criticism of

the use of music in devotional ritual. These controversial issues were of renewed interest in the Early Modern

situation of denominational strife and changed musical practices. The polyphony of choral works as well as

instrumental music no longer reliant on a textual basis stood side by side with the unisonous, jubilant singing

of the psalms of the Old Testament.

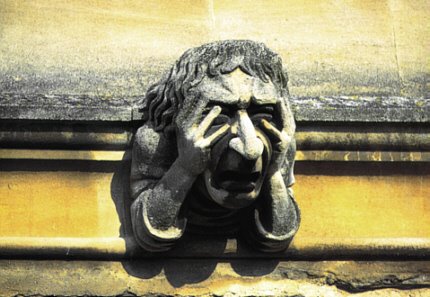

In all these contexts, the affective potential of music was marked as highly ambivalent, illustrating

the precarious human position in the cosmos – man’s bodily connection to the sensually material world and

the immaterially spiritual connection with higher reality and the Divine. On the one hand, music was

attributed an uplifting effect: music offered spiritual and intellectual edification or promised religious

ecstasy. On the other hand, music appeared as a sensual power speaking to man’s baser bodily nature,

dangerously undermining the desired rational control of the passions.

The conference “Perfect Harmony“ and “melting strains“ focuses on conceptualisations of music in Early

Modern scientific, philosophical, theological, and literary discourse. It investigates the explanatory potential

of these conceptualisations in the debate over natural philosophical questions in a time when ideas of

universal harmony were being challenged by concepts of atomic chance and chaos.

We will also explore the debates in the new sciences, the arts, and theology concerning the intellectual and affective potential of music and the ways in which ideas about music and its affective power were utilized in theological, medical, and poetological contexts for moral and didactic purposes. In addition, the conference will focus on the philosophical, literary, and musical textualisations and dramatisations of the ideas about music and its nature as an emotionally effective sensual and aesthetic experience. These issues acquire a specific poignancy in the Early Modern context, as it is an era during which ancient musicological texts were being rediscovered and new musical genres such as the opera were being invented with reference to Classical dramatic forms.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home